Introduction

One of the first things photographers must decide when venturing into astrophotography is what kind of camera sensor they’ll need to capture the beauty of the cosmos. Charge-Coupled Device (CCD) and Complementary Metal Oxide Semiconductor (CMOS) image sensors are two of the most common on the market (CMOS). Each has its own set of pros and cons that make it better or worse for astrophotography in certain situations. Further complicating matters is the ongoing discussion between advocates of monochrome and one-shot colour cameras.

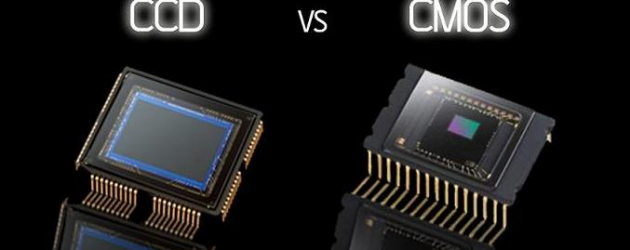

Understanding CCD and CMOS Sensors

Light is converted into electronic signals by the CCD or CMOS sensor at the centre of a digital camera. The image quality, cost, and power consumption are all impacted, but in fundamentally different ways.

CCD Sensors

CCDs have been the go-to sensors for astronomy photography for quite some time. They are well-known for the exceptional clarity and sensitivity to light of their photographs. These sensors generate low-noise, high-quality images by transferring charge across the chip and converting it into voltage in a single spot: the array’s corner. In turn, this improves light collection by allowing for a greater pixel fill-factor. CCDs, on the other hand, are typically more costly and power-hungry than their CMOS counterparts. In addition, they experience ‘blooming,’ an effect in which overcharged pixels leak their energy into neighbouring ones.

CMOS Sensors

In contrast, CMOS sensors have shorter processing times and use less power because light is converted to voltage right at each pixel’s location. They have lower manufacturing costs, making them common in smartphones and consumer-grade cameras. Their read noise and sensitivity are typically higher than that of CCDs, though. Recently developed technologies have allowed CMOS sensors to catch up to and even surpass CCDs in terms of performance, closing the gap between the two.

Monochrome vs. One Shot Colour Cameras

After settling on a CCD or CMOS camera, the next big decision in astrophotography is whether to use a monochrome or one-shot colour camera.

One Shot Color Cameras

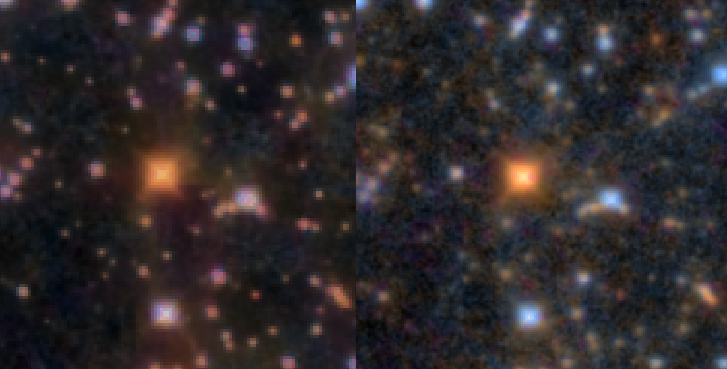

As the name implies, a One Shot Color camera takes a complete colour picture with just one click of the shutter. The Bayer mosaic used in these cameras covers each pixel with red, green, and blue filters. The greatest benefit of these cameras lies in their ease of use. Even amateur astronomers can easily take stunning, colourful pictures of the night sky with these instruments.

Monochrome Cameras

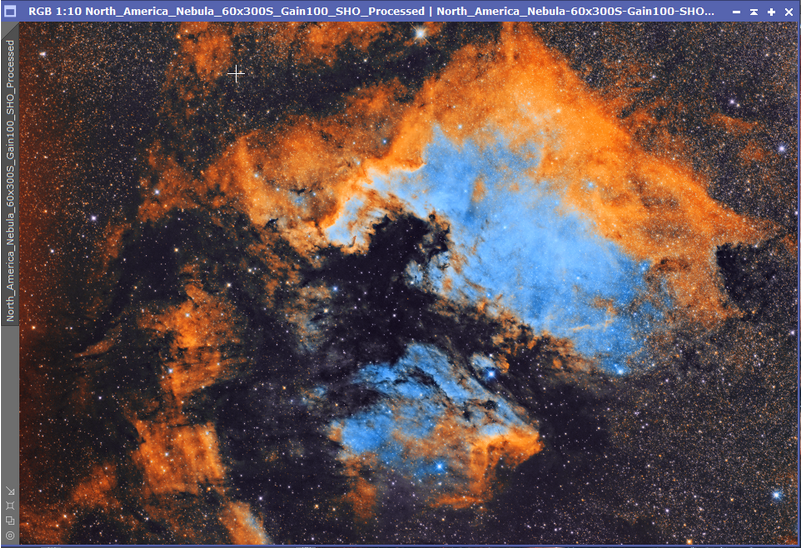

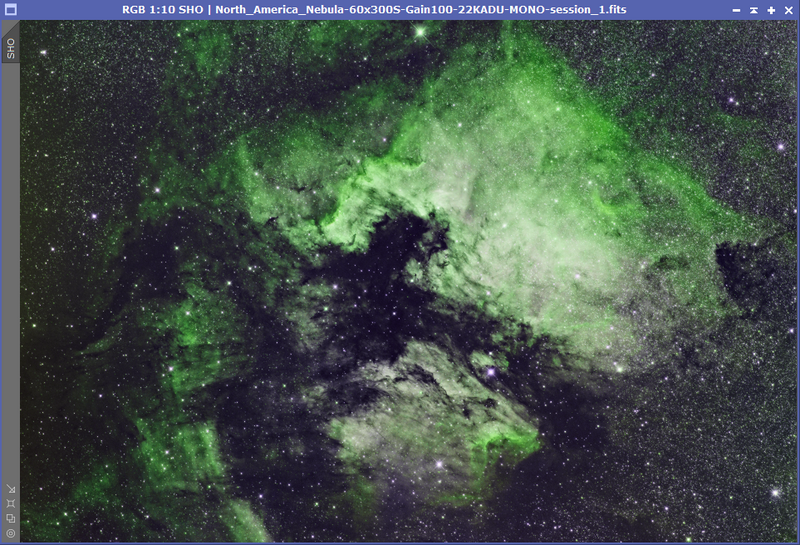

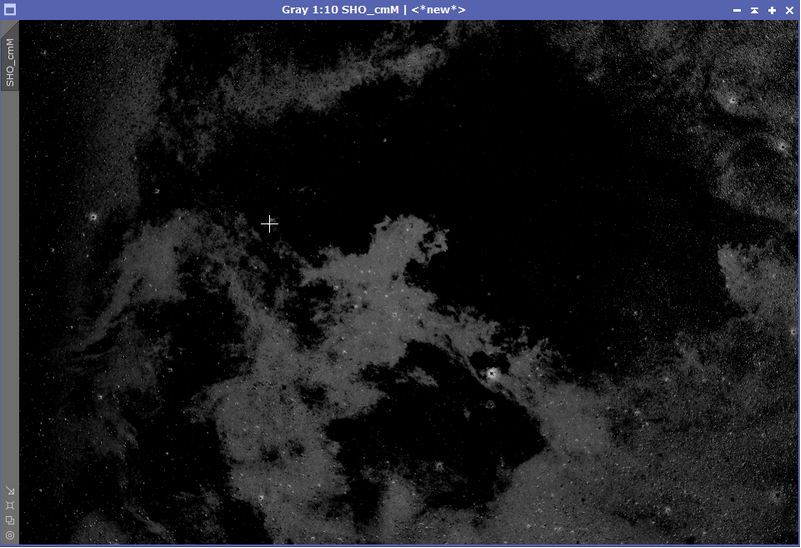

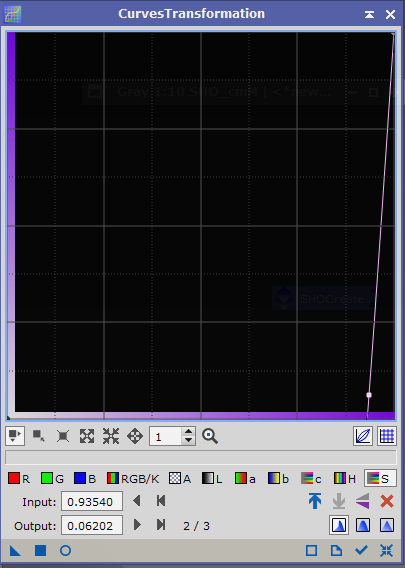

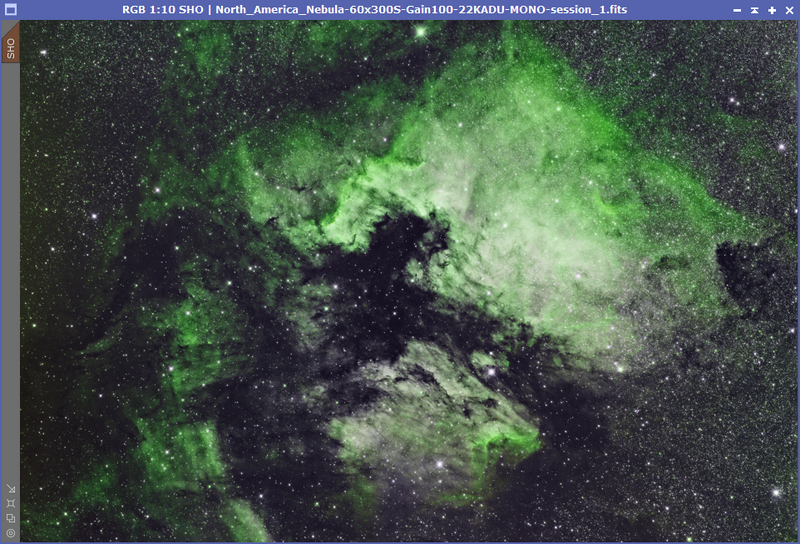

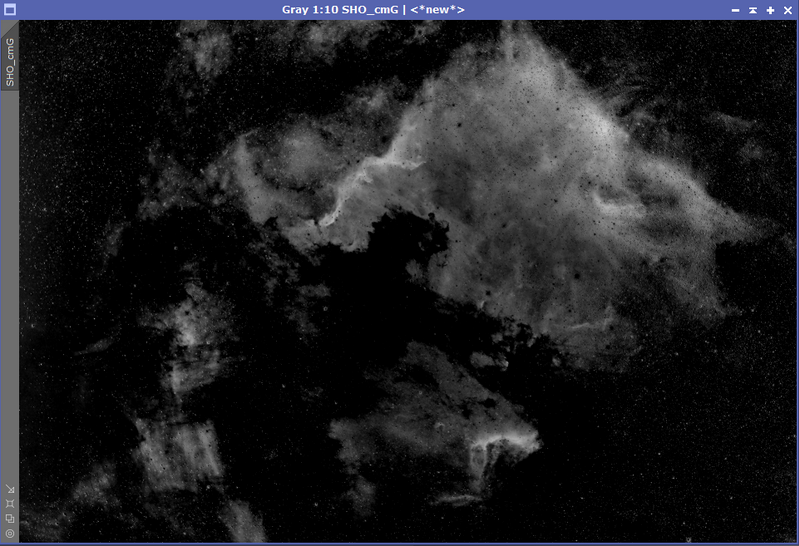

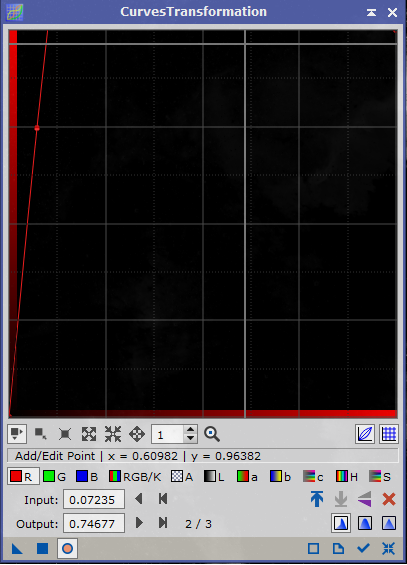

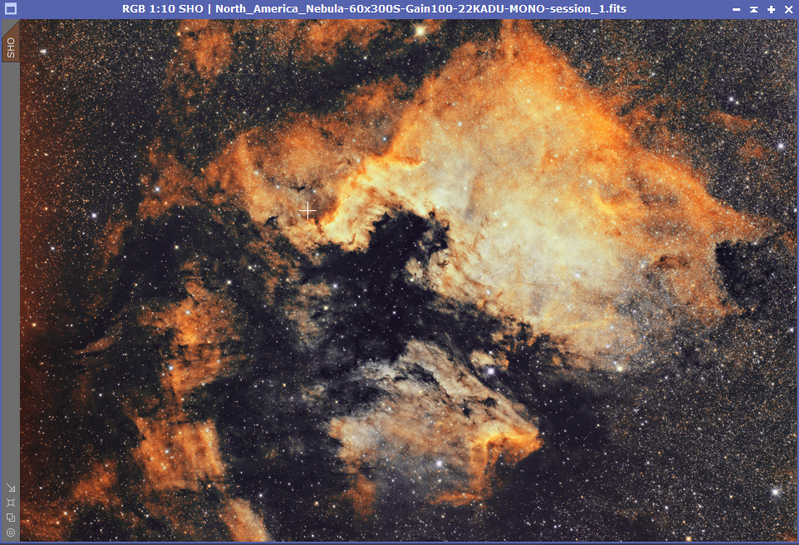

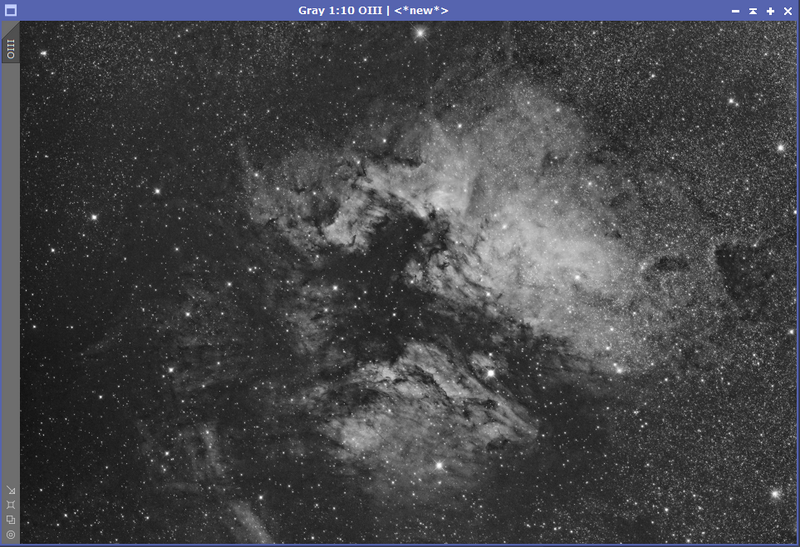

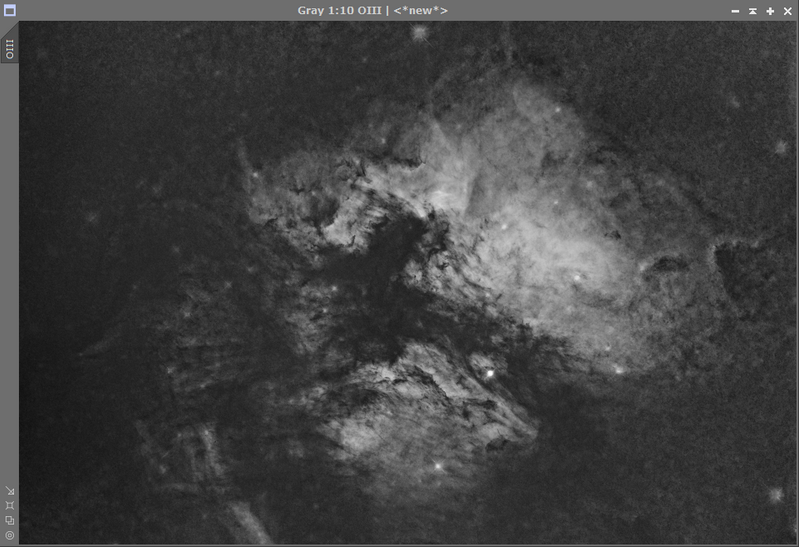

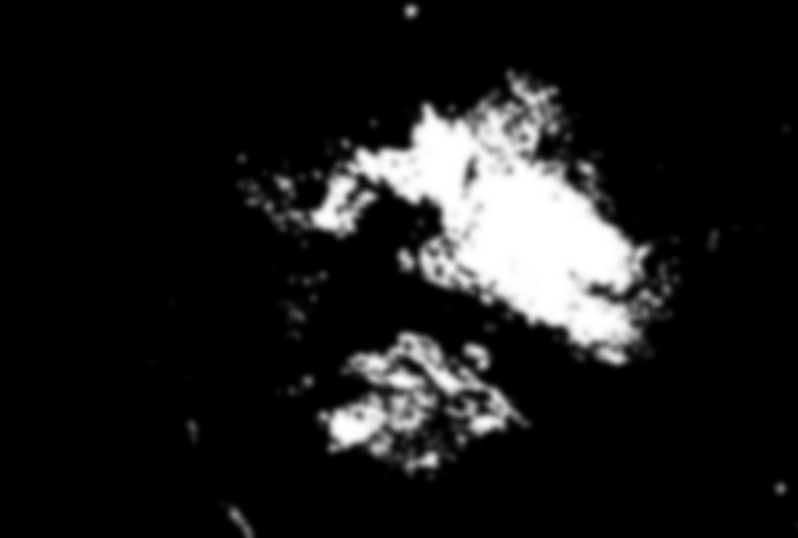

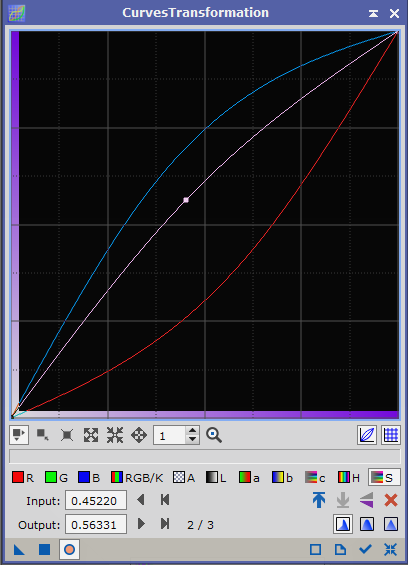

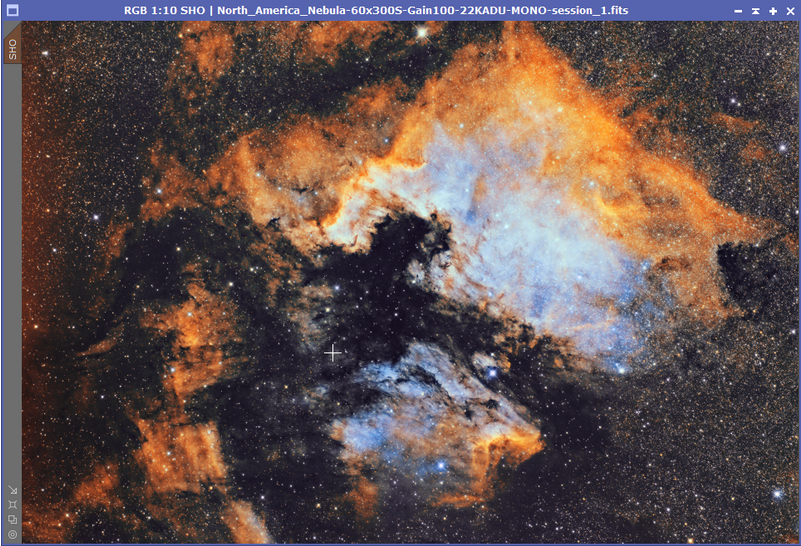

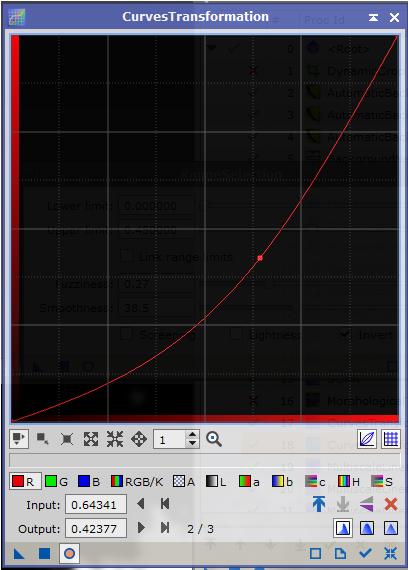

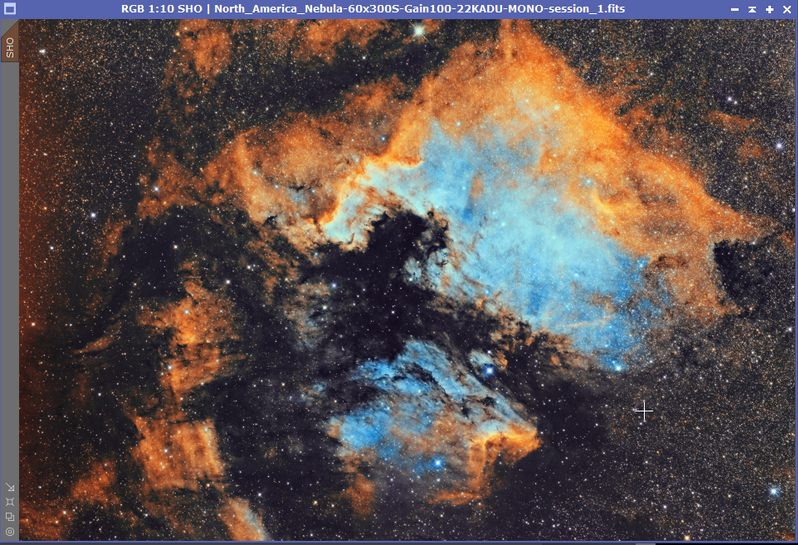

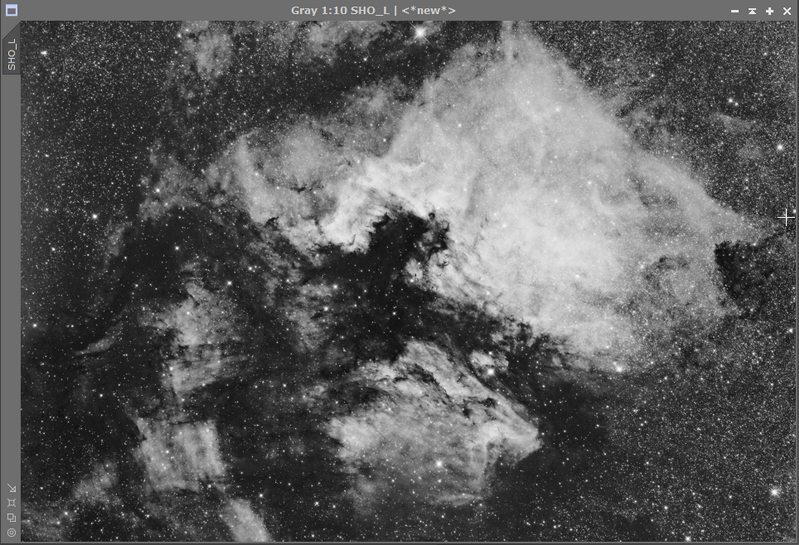

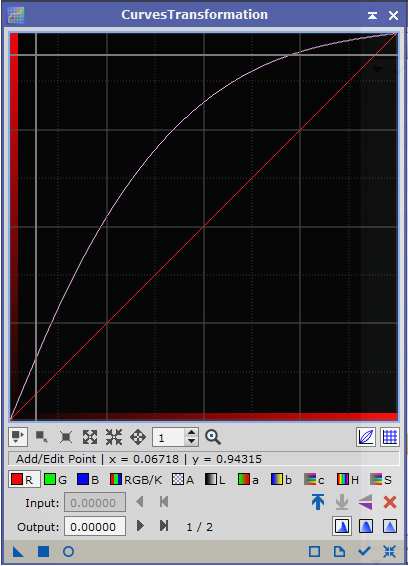

Images taken with a monochrome camera are grayscale. These cameras capture red, green, and blue light through individual filters and combine them into full colour in post-production. Even though using a monochrome camera is more difficult and time-consuming, there are some benefits.

Why Monochrome Cameras Excel in Astrophotography

In general, monochrome cameras have higher sensitivities than single-shot colour ones. They are up to three times as sensitive as cameras that use a Bayer filter because all of the light that reaches the sensor is used to create the image. This heightened sensitivities is especially helpful in low-light astrophotography.

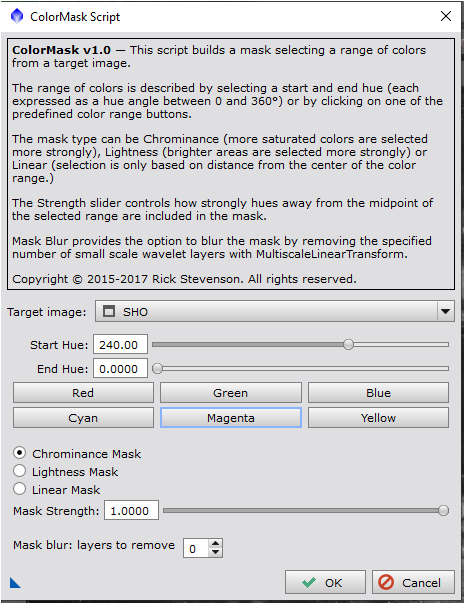

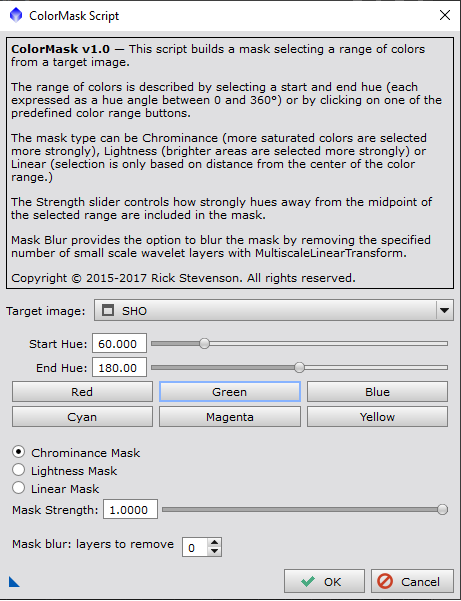

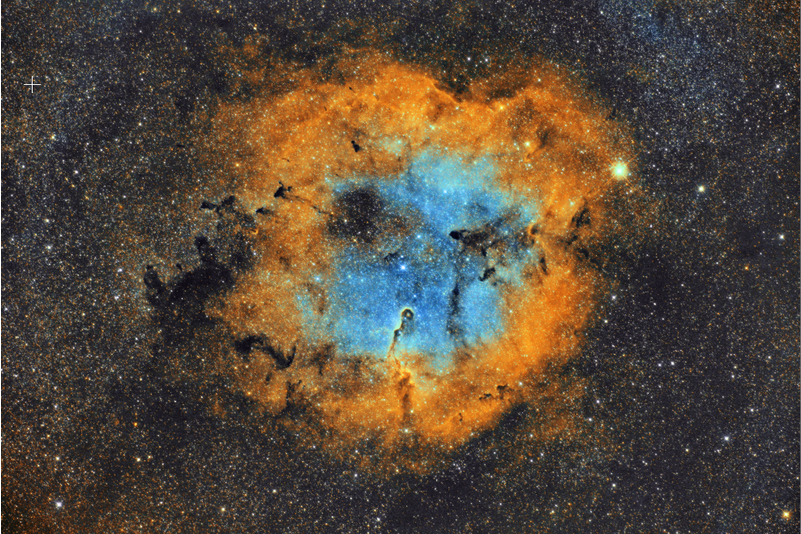

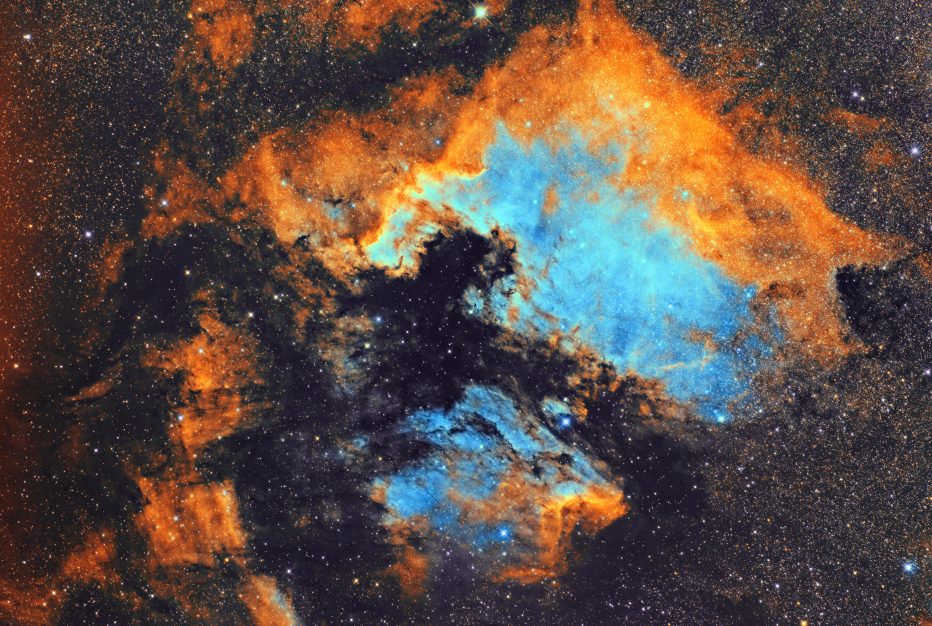

Additionally, more options and control can be had during the imaging process when separate filters are used with a monochrome camera. Using a hydrogen-alpha filter, astronomical photographers can isolate and emphasise specific wavelengths of light, such as the ionised hydrogen regions in nebulae. Imaging in light-polluted skies or capturing narrowband images greatly benefits from this ability.

Because the information for each colour channel is captured by the entire sensor rather than just a subset of pixels, as in one-shot colour cameras, the resulting images have greater resolution and detail.

Conclusion

In conclusion, CCD and CMOS sensors each have their uses in astrophotography, and the one you settle on will depend on your particular goals, financial constraints, and level of experience. Comparing monochrome and one-shot colour cameras, the former has better sensitivity, flexibility, and resolution while the latter is more user-friendly and saves time. Therefore, the investment in a monochrome camera and separate filters can be well worth it for serious astrophotographers seeking to capture the highest quality images.